We’re writing this blog at a time when most of us thought we would be done with COVID, and most of us are still working from home. In Alberta, the ICUs in hospitals have been overflowing with some critically ill patients airlifted from one hospital to another; we’ve received emergency alerts announcing new series of restrictions; the public health crisis is relentless. In the midst of the so-called fourth wave, we’ve been asking ourselves how we coped over the past eighteen months, how we’re continuing to cope, what were some of the things that surprised us, and what the new normal will look like. In reflecting on the pandemic, we see both remarkable resilience and an opportunity for positive change.

Our challenges during COVID were certainly common. We had beginning graduate students move to town, not able to meet with colleagues and effectively build their support networks. We had new scholars ship all their belongings to Canada, only to have their flight cancelled, the border closed, and engage in a nomadic existence for several months until it was possible to enter Canada. We had visiting faculty move to town only to spend their sabbatical alone. We spent our days in a continual series of two-dimensional interactions over zoom, missing the visual cues and in-person responses that lead to excitement and innovation. We missed the hallway discussions; we missed drawing squiggly lines on the whiteboard; we missed having a cadre of scholars, all in the same environment, striving for the same ideals, feeding off each other, and helping each other succeed. We missed the in-person interactions that help us understand how our research fits into the bigger picture. We found ourselves more likely to go down rabbit holes. We found it difficult to build the personal relationships that underpin our scientific collaborations. We could no longer host scientific visitors, curtailing the exchange of ideas and the development of long-lasting collaborations. We could not travel to conferences and have those oh-so-important side-bar conversations that helped us push the boundaries of our science. We found that the (sometimes) terrible internet connectivity made it difficult to participate in video chats, to attend conferences, and to give seminars. We didn’t get to see our close friends and family for extended time periods; the extra bedrooms in our homes remained empty. Those of us with kids really struggled with juggling work and life – with daycares and schools closed, it was necessary for some of us to scale back on work in order to satisfy the development needs of our children. Many of us suffered from extreme anxiety; we kept this secret because talking about our mental health is sadly (still) not the norm.

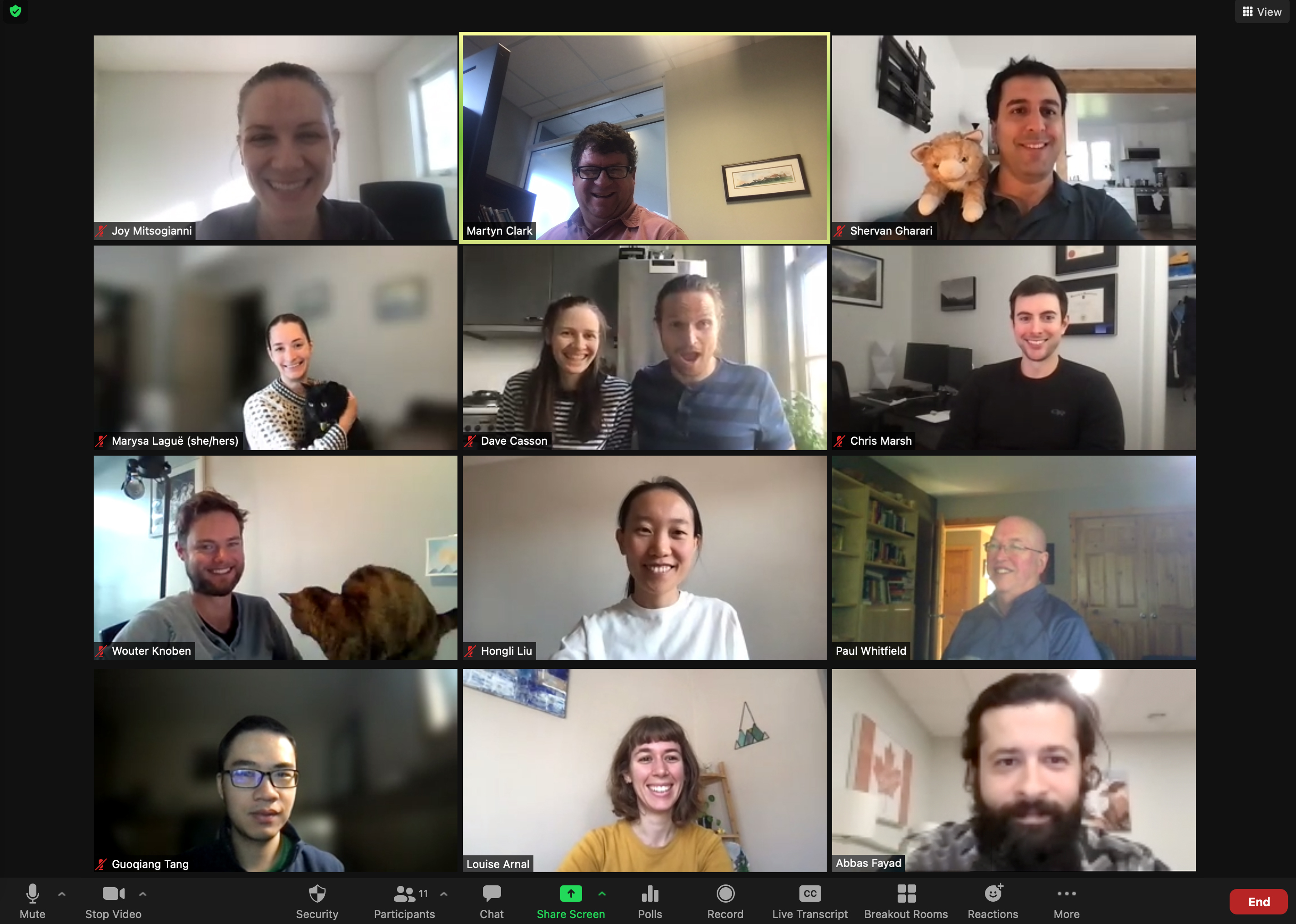

We did learn to cope; in some cases, we learned how to thrive. Of course, Canmore Alberta is not a bad place to spend the pandemic – we’re surrounded by spectacular mountains, and even with everything closed it is possible to begin adventures from our doorstep. We were able to have walking meetings. During most of the pandemic we were able to have small outdoor gatherings. We would make the time to get together over zoom for informal coffees, even having coffee meetings every day at the start of the pandemic when working from home was new and the future was uncertain. We learned to make time for more frequent small-group science discussions, both within our team and with international colleagues. The termination of travel had some advantages: the shift to online conferences meant that some of us could now attend conferences in countries where it is difficult or impossible to obtain a visa; the termination of travel cleared more time for research and family members. Some of us thrived in the home-work environment, able to take advantage of limited distractions. Many of us found it easier to connect with existing colleagues because they were online as well. On a more personal note, the zoom meetings introduced us all to each other’s pets: Poem-Poem would always place herself directly in front of the camera, meowing gently; Nova would sit quietly and attentively, mesmerized by the scientific discourse; and Sven would bark at anything that passed the house, be it another dog, a herd of elk, or the occasional bear.

As we cope with the fourth wave, hoping that the pandemic will become less intense, and hoping that we can interact more in person, it is useful to reflect on what we see as the new normal. A few things come to mind.

We expect that universities will be defined less by their bricks and mortar and more by the communities that they serve. We’ve seen an explosion of interest in our graduate classes – the pandemic meant that we could open classes to students from all over the world (e.g., in one example, our graduate course on process-based hydrological modelling engaged 91 students from 16 different countries around the world). The initial data from the shift back to in-person learning demonstrates that classes offered online are much more popular than classes that are only offered in-person. Indeed, these experiences were evident before the pandemic where lecture halls were empty in universities that offered an online option. On the one hand, the shift to online learning means that it is possible to take advantage of the best expertise from anywhere on the planet; on the other hand, the shift to online learning also erodes the vibrancy of university campuses. This opens up a suite of new questions: To what extent will the desire to attend a given university be shaped by the pedigree of the institution, the expertise and research accomplishments of the professoriate, and the content of the curriculum? To what extent will universities be defined by their research and teaching? Given the shift to online learning and pre-built online modules (recorded lectures etc.), what is the role of professors in the learning experience? What is the willingness of students to pay for an online learning experience? To what extent will academic qualifications be offered by a single university or a consortium of universities? More generally, does the shift to online learning expand the communities that universities can serve?

We also expect that we will travel less. For many of us the termination of travel caused us to take a deep breath, sit back, and for us to ask ourselves if our travel was really necessary? Do we really need to travel to another university to serve as the external examiner on a thesis defence or to give a research seminar? Do we really need to travel to a different city to serve on a proposal review panel or to serve on an organizing committee for a conference? Do we really need to travel to meet with our colleagues in government departments? Clearly the distinction is not dichotomous and is a matter of degree. We value the opportunity to meet with colleagues, to build professional relationships, to improve our understanding of the research problems, to understand the broader context underlying individual research problems, to brainstorm, to share ideas, to co-develop new research projects, and to find solutions. Yet we understand the cost that travel has on the environment, our individual professional contributions, and our family life. We expect that we will be more strategic and judicious in accepting travel opportunities as we transition to the new normal.

We also expect that working remotely will be more common and more accepted. Does it really make sense to spend an hour or two commuting to work when we can work effectively from home? Is it necessary to commute to work every day? To what extent is it possible to work from a different city for family or lifestyle reasons? To what extent is it necessary for institutions to provide office space when their employees can work remotely? Like travel, we need to better balance the value of in-person interactions with the benefits of remote work.

Finally, we expect that we need to be much more effective in building professional relationships online. In the past few years we have witnessed the good, the bad, and the ugly of social media, and we’ve certainly seen the importance of social media during the pandemic. For example, we created a Twitter account (@CompHyd_Earth) to stay connected with other research groups and the wider community. But social media is often used for somewhat shallow unidirectional communications; an opportunity to share experiences and advertise accomplishments (e.g., “hey peeps, look at the paper I just published”). The new normal will demand that we are much more effective in building strong professional relationships online – for example, collaborating on a grant proposal with people you have never met in person; building vibrant journal clubs to discuss recent science advances; getting together with colleagues to discuss the unsolved science problems in our field. Such substance will matter and will help us define the scientific community of the future.

The pandemic has certainly provided a time for reflection and an opportunity for positive change. We’ve seen that universities have been able to effectively respond to the changes required by the pandemic, a combined effort of university administrators and the professoriate. Universities have not only risen to the occasion to meet their traditional functions; universities also are rising to the challenge to serve a myriad of communities beyond traditional university campuses. Consortiums of universities will undoubtedly be much more common in the future, building on the successes of the CUAHSI virtual university in the USA and the western Dean’s agreement in Canada. More generally, the continual evolution to remote working relationships has the potential to produce a more effective academic culture.

Since we all have a responsibility to be proactive in shaping the “new normal”, this begs the questions: Which aspects of COVID would we like to keep in the future; how can we improve the academic community? A key positive change is pivoting from an academic community that is fiercely competitive to one that is collaborative and supportive. We’ve seen some elements of this during COVID. Such evolution requires recognizing the heterogeneous contributions from the academic community in ways that look beyond traditional quantitative metrics of success (e.g., see the Declaration on Research Assessment). The evolution requires taking better care of each other’s mental health and helping each other thrive. The evolution requires that we all do our part to make the world a better place.

In closing, dear reader, please take a moment to imagine the world that you’d like to live in; imagine some specific steps that you can take to create the world that you want. Onward!

USask/Canmore Computational Hydrology at CWRA 2022: things not to miss!

Posted on 05 Jun 2022

USask/Canmore Computational Hydrology at EGU 2022: things not to miss!

Posted on 15 May 2022

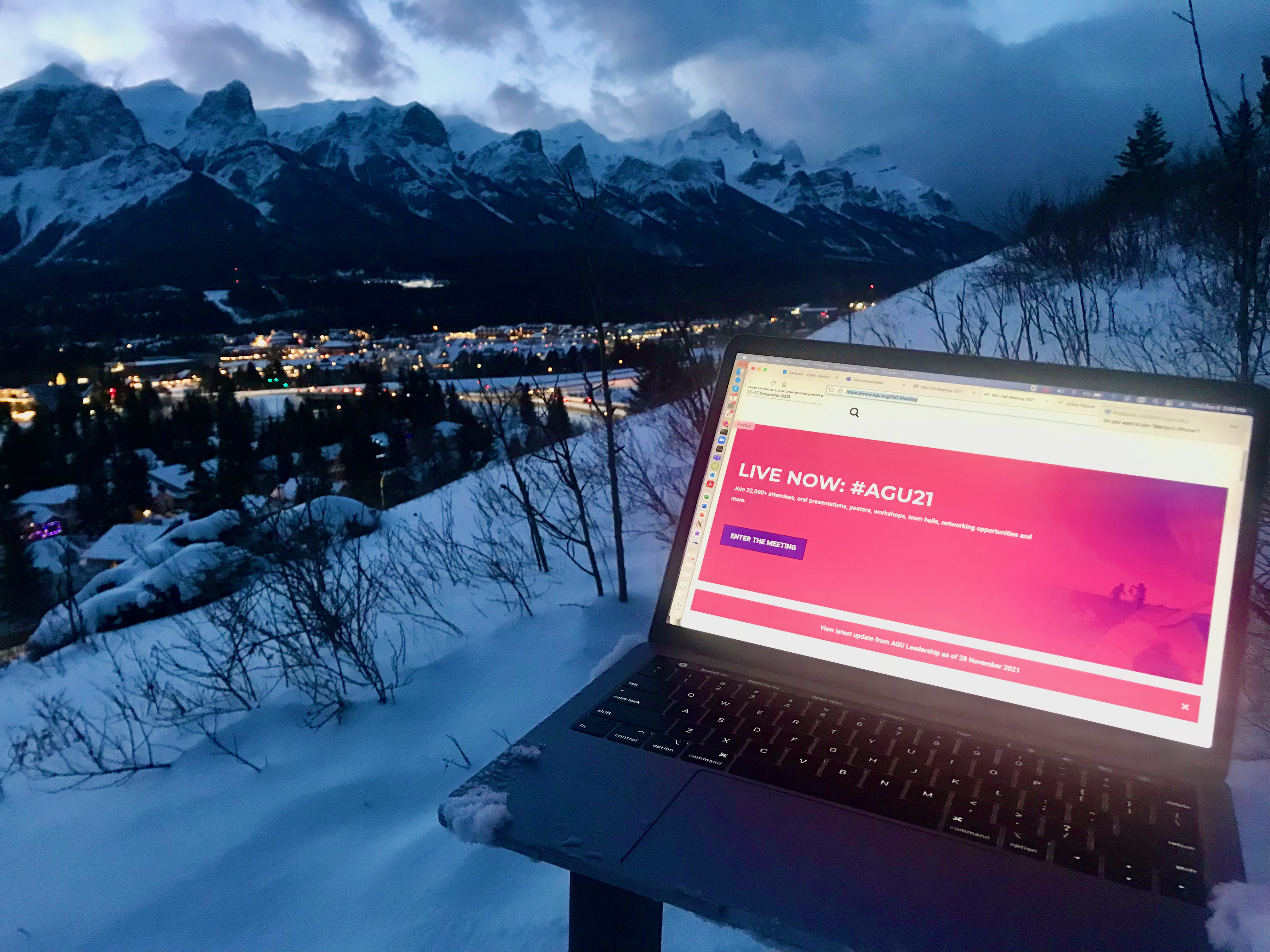

USask/Canmore Computational Hydrology at AGU 2021: things not to miss!

Posted on 10 Dec 2021 Posted on 01 Oct 2021

Posted on 01 Oct 2021